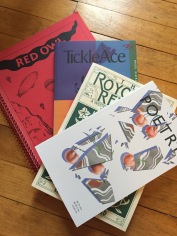

IDEA #105. Go to a library and read from cover to cover a poetry or literary magazine. Granta would be a natural choice, but there are hundreds “little” magazines, some “important” and others less so, that publish poetry and short fiction, sometimes along with photography and other visual art. If you want to submit something that you have written or created, pat yourself on the back. If it’s accepted, get someone to take you out to dinner in celebration.

For all that we read that the people of the United States are low on literacy and debased in their cultural interests, the fact remains that Americans are a manically active people when it comes to writing and publishing poetry. Many universities publish august “reviews” containing poetry, prose, and literary commentary, and a glance at the section of poetry magazines on the shelves of any large bookstore reveals many, many independent reviews, poetry magazines, and literary quarterlies. Poetry is being written, and poetry is being published.

For the youngster with an interest in poetry, the discovery of these magazines can be a revelation—a window into a world of creativity and verbal dexterity and, more importantly, a whole choir of new voices to be heard. A typical  periodical—and Granta is among the better known—rewards a slow and careful reading, with some contents requiring deep and immediate concentration while others can be set aside for another time. Even the little biographical blurbs on the writers can be of interest—who are these people, and where do they come from?

periodical—and Granta is among the better known—rewards a slow and careful reading, with some contents requiring deep and immediate concentration while others can be set aside for another time. Even the little biographical blurbs on the writers can be of interest—who are these people, and where do they come from?

While it is true that many published poets are university-affiliated academics, there are enough unattached citizen-poets to remind the reader that poetry has been a popular and democratic art form since the days of Homer. A number of the smaller of the “small” magazines that specialize in poetry are themselves distinctly demotic in form, with production values taking a back seat to the sheer cramming in of contributed work. Here is poetry at its most raw, and here might lie the opportunity for a young poet to take a first step into the world of the aspiring poet—to complete the “final” draft of a poem or two.

In the past and still in a few cases, the poet’s next steps were to write the cover letter, to fold the obligatory self-addressed stamped envelope, and to stuff them all into an envelope in the form of a submission. Nowadays most poetry magazines solicit and receive submissions via email; it’s even fair to say, despite the “hands-on” urgings of this post, that there are as many online poetry and literary ‘zines as there are ones still in print.

The fortunate young poet will receive the overwhelmingly gratifying news that a poem—or two, or three—has been accepted for publication. As anyone who has ever read a literary autobiography knows, the arrival of one’s first acceptance is often the event that inspires a career.

It might also be happy case that the young poet’s school sponsors its own literary magazine, creating the opportunity not just for submission and publication but also to engage in editorial work—selection and curation, copy-editing, and preparation for press. Many famous writers got their start by publishing in and then working on school and college literary magazines.